1. Introduction

The word “curriculum” is used in various ways in educational literature.[1] Here we use the term to refer to the entire “racecourse” or program of learning that we design for our trainees.[2] Thus, our curriculum includes courses (subjects) set in sequence. But developing a curriculum —in its fuller sense—involves many other consideration. Developing our curriculum—in its fuller sense—involves many other considerations. In the sections that follow, we explore the eight curricular elements[3] listed below.

- End Point: a specific end, involving both a vision and aligned educational goals

- Participants: well-defined participants, including the trainees and trainers

- Contexts: well-defined contexts in which our curriculum functions, including essential cultural elements and associated educational concepts

- Principles: core educational convictions that give rationale for what we offer and how we design it

- Content: the scope of subjects and skills that we cover, including their best sequence

- Resources: resources we provide to help our trainers teach well and trainees learn well

- Evaluation: how we will evaluate this program’s effectiveness in design and delivery

- Action Plan: a concrete plan for developing and implementing the content proposed

In the sections that follow, we explore each briefly as we develop a curriculum for non-formal theological training for global use.[4]

2. The End of our Curriculum: Vision and Goals

We must first define the end of our racecourse. Where are we taking our trainees? The answer includes our vision for what our overall program of courses must accomplish and the educational goals that will realize that vision.

2.1. Vision for Trainers and Trainees

Our program of non-formal theological training must contribute to our organization’s overarching vision. The vision of Training Leaders International (TLI) is “to establish and strengthen local churches and their leaders around the world.”[5] TLI uses two means to accomplish this vision, like two edges of a single sword: (1) TLI mentors and sends people who already have theological training (2) to train pastors and other Christian leaders around the world who have little or no access to theological training, who in turn will train other indigenous leaders.

Our non-formal program of theological training likewise has a double-edged vision. At the end of our non-formal program, we envision two types of people emerging:

(1) trainers who, through easy-to-use resources for TLI’s non-formal training environment, are equipped to guide untrained pastors and leaders around the world in face-to-face learning with cultural and educational sensitivity;

(2) formerly untrained pastors and leaders around the world who, through the Bible, humble confidence in God and his Word, and foundational skills and knowledge, are equipped to preach or teach any part of God’s Word accurately and relevantly and to equip others to do likewise.

Our program of non-formal education must be driven by this double-edged vision. Our discussions below of curricular participants (§3) and resources (§7) will reflect both edges. Now, in §2.2, we will focus on the creation of educational goals only for our trainees, for it is the trainees whom the curriculum designers and trainers together seek to bring to the envisioned end.[6]

2.2. Educational Goals for Trainees

We must set specific, measurable goals that, when reached, enable the trainee side of our double-edged vision to be realized.[7] The following five educational goals advance our vision (above) for our trainees. By the end of the course of study, our trainees will have gained:

-

- a sound understanding of the unified and diverse content of the Bible;

- the ability to use basic interpretive principles to rightly understand any type of passage in the Bible;

- a sound grasp of fundamental theological categories;

- a basic ability to communicate any type of passage in the Bible with clarity and relevance; and

- a basic ability to train others in these skills and knowledge.

Within the remainder of our philosophy outlined below, we will see how vital the end is as we develop ways to help our trainees run the course well, meet these five goals, and attain the vision.

3. Participants in our Curriculum: Trainees and Trainers

We must now specify the participants in our program of courses. These include the trainees whom we help to achieve the five specified goals above. These also include the teachers/trainers whom we equip and deploy to help the trainees achieve the goals. In our context, both groups of curricular participants are highly diverse—and that matters for what we design and how we design it. [8]

3.1. Trainees

Our trainees are strikingly varied. They are diverse in language; culture; worldview; geo-political situation; socio-economic position; possession and availability of resources, in general and specifically in theology; religious upbringing; religious majority context; daily safety; pressing life struggles; age; gender; educational level; educational style; learning style; primary occupation; church involvement; Bible knowledge; type and depth of theology.

religious upbringing; religious majority context; daily safety; pressing life struggles; age; gender; educational level; educational style; learning style; primary occupation; church involvement; Bible knowledge; type and depth of theology.

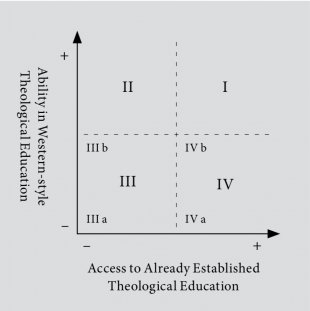

The chart (right) shows four quadrants into which potential trainees can be divided. Each quadrant demands a different response in theological training. The horizontal axis depicts how little (–) or much (+) access they have to already established theological education. The vertical axis depicts how little (–) or much (+) ability they have in Western-style theological education.

(NB: the + and – symbols convey quantitative levels in these categories, not qualitative value.)

Quadrant I is not the target of this curriculum of non-formal training. TLI’s department of formal training targets Quadrant I.

Quadrant II, however, is our primary target area. This is for two reasons. First, our non-formal department’s mission is to bring theological training to those with little or no access to such training. Thus Quadrants II and III are our primary targets. Second, our curriculum team and trainers are currently better equipped to design and deliver more Western-style training, which places us more comfortably in Quadrant II.

For the second reason mentioned above, Quadrants III and IV are more complicated for us to work within than is Quadrant II. In contexts III and IV, more significant ethnographic research and changes to Western curriculum structure and delivery methods are necessary for meaningful learning. That said, there is a spectrum in Quadrants III and IV. People in IIIb and IVb are somewhat more able to cope with more Western-style design and delivery than people in IIIa and IVa. As Western aspects of curricular design and delivery are toned down, and as trainers’ cultural sensitivity is increased, the learning experience of the trainees in IIIb and IVb will be enhanced.

To be realistic and frank, staff at TLI are simply not equipped to train people in IIIa and IVa. The educational styles are too divergent. However, we can meaningfully grow in our effectiveness in training people within IIIb and IVb, and we must, for they come to our non-formal training with those from Quadrant II anyway.

Our trainees are diverse, coming from Quadrants II, IIIb, and IVb. Thus, and as is explored and addressed in §3 and §6, TLI’s curriculum team and trainers must continuously grow in cultural and educational sensitivity if we are to design and deliver an effective curriculum of non-formal theological education. Then we can better meet the various needs of our diverse trainees.

3.2. Trainers

Our trainers are also variegated. They have diverse levels of investment in TLI, as some are full-time International Trainers (ITs) and most others are occasional Associate Trainers (ATs). Our ATs are diverse in types of employment outside TLI: professors, pastors, seminary students, laity. ITs and ATs come with various levels and types of education: Ph.D. and D.Min., M.Th. and M.Div., B.Th. and other. Our trainers have diverse amounts and types of cross-cultural experience. They have different levels of experience with TLI itself. They have a range of expectations of what they will and want to gain from a trip.

This range of trainers carries curricular consequences. Their ability to craft lesson plans is on a spectrum, as is their capacity to engage trainees in educationally and culturally sensitive manners. These spectrums of abilities demand various levels and types of resourcing, training, and mentoring in order to adequately equip each trainer—which is half of our double-edged vision—to best help our trainees attain the end.

4. The Context(s) in which our Curriculum Functions

We must now specify the context(s) within which our curriculum functions. Context is significant for a curriculum’s design and thus for a delivery that is intentionally harmonious with its content. Despite our grossly diverse contexts (from Haiti to Romania to Tanzania to India, etc.), a few significant unifying features do emerge. All our trainees are (1) adults, (2) not indigenous to the US, and (3) primarily oral-preference learners. These common features of our curricular context(s) are educationally significant for the design and delivery of our curricular content. They demand engagement with topics such as andragogy, cultural dynamics, and orality in the process.

Below are a few classroom-specific principles extrapolated from engaging scholarship in these educational and cultural categories. A central theme will emerge: our curriculum team and trainers must deliberately and constantly increase our understanding of how our trainees learn best, for this touches curriculum structure and design as well as teaching strategies.

4.1. Adult Learning (“Andragogy”)

Andragogy is the art and science of “leading adults” in learning. It is significant that we are training adults.[9] Differently than children, adults tend to seek training because they have particular needs and interests; they are interested in “subjects” insofar as these address life-situations; and they have many experiences that are significant learning resources. Below are four examples of andragogic principles that affect how we develop curriculum for adult learners.

First, our adult trainees will learn more effectively if their perspectives of their own learning needs are heard, engaged, and thereby valued.[10]

Thus, while our curriculum team and trainers set the program of courses that we deem strategic for meeting our trainees’ needs, we must pay constant and increasing attention to their perspectives on their own needs—both through research and personal engagement.[11]

Second, course material and even titles will better resonate with adult learners if they are expressed and approached more like active life-situations than abstract, static subjects.

According to Ott, “The content of adult education is less determined by the subject matter of classic courses and more structured around problems and challenges relevant to the (adult) learner’s life and work.”[12] Thus, course titles can be worded like active life-situations rather than static subjects (e.g., our combination of theology, bibliology, and ecclesiology becomes “Knowing God, Scripture, and Ourselves”). And course content that traditionally covers issues topically as author/recipients/date/occasion is covered by asking questions that correspond to ordinary life situations: e.g., Who wrote this? Why? What was going on? (See §5 below.)[13]

Third, effective teaching methods for adult learners include both lecture, which provides categories and knowledge to help trainees analyze their experiences,[14] and participation-based active learning moments.

It is crucial to help adult trainees actively reflect on their past experiences and actively plan for future experiences in light of the new categories, frameworks, questions, and material; therefore, lecture is a crucial ingredient of adult learning. Yet their learning experience must also involve active, humble, and inquisitive discussion of what they are experiencing and struggling with, how they might apply insights from the present course to their life-situations, and how the previous course’s insights actually affected their experiences (or not).[15]

Fourth, adult learning must incorporate the whole person: their perspective and knowledge (cognitive domain), their emotions and hopes (affective domain), and their concrete plans and actions (practical domain)—all set within a communal sensibility.

Merriam, Caffarella, and Baumgartner, in their newest edition of Learning in Adulthood, have a welcome addition on non-Western andragogic insights.[16] Comparing education based in Confucian, Hindu, Maori, Islamic, and African indigenous perspectives, they argue: “In non-Western traditions, education and learning are in the service of developing more than just the mind. They are also to develop a good person, a moral person, a spiritual person, one who not only contributes but also uplifts the community.”[17] Non-Western education also tends to be “interdependent, communal, holistic, and informal”[18]—the last meaning “embedded in everyday life” and “lifelong.”[19]

The principles of adult learning mentioned above, and especially those which have taken shape in research in non-Western contexts—similar to nearly all of our contexts—must affect our curricular design and delivery. The same is true regarding certain cultural patterns and their effect within cross-cultural educational contexts—similar to all of ours. I will now outline a few crucial cultural categories.

4.2. Crucial Cultural Categories

P. Hiebert, R. D. Shaw, and T. Tiénou, among numerous other cultural anthropologists and missiologists, have tried to describe essential quests or longings that transcend cultures.[20] Yet cross-cultural educationalists sometimes express that “almost no practices [have been] found that could be implemented globally.”[21] This is because culture deeply influences “the way we perceive, organize and process information,” “the way in which we communicate, interact with others and solve problems,” and “the way we form ‘mental categories’ and retrieve them in order to create patterns which allow us to generate new knowledge by means of previously acquired knowledge.”[22] All of this necessarily affects students’ preferences for, values for, and deeply ingrained abilities in various types of “thinking, relating to others, and… classroom environments and experiences.”[23]

Many teachers get frustrated with student responses and patterns in cross-cultural classrooms, while others sense an occasional disconnect with trainees but cannot put their finger on what is not quite working. Many of the responses, patterns, and disconnects are rooted in deep and pervasive (and well-documented) cultural features. Some curriculum developers have not designed and produced material that aids teachers well in such non-Western education contexts. Key cultural categories can and must be explored by our trainers and curriculum team if we are to be increasingly effective in our contexts.

Some cultural categories are more pertinent to short-term educational contexts than others. The following cultural issues should be prioritized:

- How does communication happen? (e.g., high context vs. low context)[24]

- How are wrongs conceived and dealt with? (e.g., guilt–innocence; shame–honor; fear–power)[25]

- How do people relate to others and to learning itself within an education environment? (e.g., power distance; individualism–collectivism; uncertainty avoidance)[26]

- How do people relate tasks and relationships to time? (e.g., monchronicity vs. polychronicity)[27]

Each of these major cultural categories has implications for how our trainers can conduct a classroom environment in an educationally and culturally sensitive manner within our curriculum of non-formal training in our cross-cultural context(s). How we design our curricular material for these contexts can aid or hamper our trainers. (See §6 below.)

4.3. Orality and Literacy

According to the Lausanne Movement, “70% to 80% of the world does not depend on textual transmission; they depend on aural, or oral-visual, means to receive, process, remember, and pass on information.”[28] In contrast to this, and in relation to curricular issues, D. Sills observes that “over 90 percent of all our tools for evangelism, discipleship, and leadership training has been produced for highly literate people.”[29] Following W. Ong’s influential book, Orality and Literacy,[30] R. Arnett points out that “Today, we understand that orality is not simply the inability to read and write a spoken language”; rather, there are “significant cognitive and sociocultural differences” between oral and non-oral peoples.[31] Oral and non-oral people “store information differently”: non-oral people in written and thus semi-permanent form, oral people in active memory. Oral and non-oral people also “organize information differently”: non-oral people “in a subordinate and analytical manner”; oral people “using perceptual, concrete, functional categories through mnemonic devices such as repetition, narrative, song, and drama.”[32]

Most of our trainers tend toward literacy-preference learning; however, most of our trainees are oral-preference learners. Due to our training contexts, then, we must take seriously this danger: oral learners are disadvantaged in and sometimes even excluded from text-heavy learning.[33] This has major implications for our curriculum, particularly in the resources we provide. For example:

- In their initial taste of theological education, face-to-face learning situations will benefit our oral-preference learners more than written material. So, in the first instance, we must focus our time and resources on better equipping our trainers for face-to-face encounters. (This focus will help meet the first aspect of our double-sided vision above, which in turn better meets the second aspect of our vision—see §2.1 above.)

- We can provide short, “bare bone” written material for the trainees, even at first. This will be helpful for trainees and trainers, and especially for oral-preference learners if it contains understandable, memorable, repeatable key phrases—and perhaps associated images (although images, symbols, and colors are notoriously culture-specific).

In §4 we have briefly analyzed the context(s) within which our curriculum functions. Issues of andragogy, cultural dimensions, and orality are particularly pertinent to our philosophy of curricular design and delivery within concrete context(s).

5. Principles of Education Shaping the Content of our Curriculum

Now we must clarify some key principles of education that shape the content of our curriculum. These provide the why that underlies what we offer and how we offer it to our trainee-participants to help them reach the five goals. We will mention three such principles that govern our content design and course delivery. At each point below, we will mention how the principle works regarding the entire scope of content and within individual courses.

5.1. Go Deeper in Fewer Areas

In our overall scope of content, we focus our training on understanding and communicating Scripture. This distinguishes us from training organizations that seek to be comprehensive in their scope of leadership training but which, as such, can merely touch on training in interpreting and communicating Scripture. Our first principle of education is to go deeper in fewer areas.

In our individual courses that are focused on interpreting and communicating passages within a certain genre (Courses 3–8, see §6 below), we choose one representative book and do not attempt to cover every passage within it. We select a few passages within that book, in order to focus in depth on the skills of understanding and communicating that type of biblical material. (Discerning a book’s whole organization and message is inherent in responsibly understanding a passage within it and is therefore incorporated into the exploration.) Selection of fewer items enables a deeper grasp and development of the skills and knowledge necessary to the task.

This approach protects trainers (and thereby the trainees) from a few common temptations. When there is too much material, trainers—especially less experienced ones—are tempted to rush to “get through” everything. They typically default to lecture and thus mainly pass along abstract content and neglect to give concrete practice in skills. Lecture, content transfer, and abstract ideas are all helpful aspects of learning, but they are not conducive to deep learning on their own.[34]

A further danger arises from such temptations to cover too much material in insufficient depth and manner. A teacher’s approach presents a “hidden curriculum”, which P. Shaw explains as “the potent sociological and psychological dimensions of education, which are usually caught rather than intentionally taught.”[35] Educational sociologists have documented that “the hidden curriculum generally overrides the explicit curriculum.”[36] In fact, “sadly, this hidden curriculum often trains our students in the exact opposite way to that which we teach in our explicit curriculum and claim in our purpose statements.”[37] Indeed, the abstract, content-driven, lecture-only approach outlined above undercuts our explicitly skill-oriented goals (goals 2, 4, and 5; see §2.2 above). But the temptation toward such an unhelpful approach is reduced and held in check, if not completely avoided, if we adopt the explicit educational principle of going deeper in fewer areas.

5.2. Focus on Skills While Being Rich in Content

Foreshadowed in our previous educational principle, and regarding our overall curricular focus, our goal is not knowledge per se; it is the use of knowledge and skills in an activity: e.g., preaching, teaching Scripture. Therefore, acquisition of skills must be our explicit focus. That said, if there is no good, right, and rich content, the use of said skills is dangerous. Our vision for the indigenous pastors/leaders (§2.1) is for them to catch fish on their own, so to speak—i.e., to understand and communicate Scripture without additional resources (including ourselves)—and for other “generations” of indigenous pastors/leaders to catch fish on their own as those whom we train pass the skills on (as in 2 Tim. 2:2). Our explicit focus is therefore on the skills involved in hermeneutics, exegesis, and communication. At the same time, we embrace the fact that this process necessarily and gloriously involves rich content beyond the mechanics of exegesis and teaching.

In individual courses, there is a rhythmic focus on how to understand and how to communicate Scripture with others. They are skill-focused. Our educational principle above (§5.1), focusing in depth on a few passages, enhances the possibility of skill acquisition, for it creates time and space for concrete experimentation, practice, and the experience of success in the practice of the skill—all of which are essential to deeply acquiring a skill.[38] That said, the passages that are selected are carefully chosen for their theological potency so that the discussion and practice of skills always involves a furtherance of specific and fundamental theological content.

5.3. Engage the Text (with Orientation), then Theology

In our overall focus, we want to communicate through our explicit curriculum (i.e., what we say we are doing) and through our actual implementation (i.e., our implicit or hidden curriculum) that exegesis is proper, not eisegesis. Thus, our curriculum must encourage the trainees to engage the text of Scripture quickly and directly, moving to theological synthesis and application in light of the text, not the other way around. So, we delay full theological synthesis[39] (e.g. Biblical Theology proper, Systematic Theology proper, Practical Theology proper) until after we engage the text.

In individual courses, this educational principle is matched. Reflection on theological themes within a biblical book comes after work on the texts themselves. We engage the text first before undertaking a full theological synthesis and application.

A caveat is needed. Theology and exegesis are related somewhat cyclically. Each sharpens and informs and confirms the other. Thus, some basic theological orientation to the text is helpful. This is especially helpful in our contexts since many of our trainees tend toward two problems: some have little creedal and biblical literacy; others possess Bible knowledge but in disconnected fragments with no sense of Scripture’s overarching coherence or God-centeredness. This means that while we delay any sense of full theological synthesis until after exegesis, some theological orientation is helpful initially (as long as it is still textually-based): namely, orienting ideas about God, about Scripture, about ourselves as stewards of his Word, and about the Bible’s basic storyline as it reveals God’s plan of reconciliation in Christ from Genesis to Revelation. Even within these orienting precursors to exegetical training, our educational principle of engage the text, then theology is stated (explicitly) and demonstrated (implicitly) at all times.

6. The Content of Our Curriculum: Scope and Sequence

We have explored our curriculum’s end vision and educational goals (§2 above), the diversity of our curricular participants including trainers and trainees (§3 above), key aspects of the contexts in which our curriculum functions (§4 above), and our foundational educational principles that undergird what we do and how we do it in our overall focus and in particular courses. We may now define the scope of content and skills that arise from these explorations, including their most helpful sequence. The entire scope and sequence of courses, including their content and skills, will meet our educational goals and help our trainees to reach the end-vision.

6.1. The Scope of Skills and Knowledge

Because of our vision and educational goals, each course targets the development of certain (1) exegetical skills, (2) theological knowledge, and (3) communicative skills. The desired cumulative effect of our entire 9-course curriculum of non-formal training is that the trainees acquire foundational skills and knowledge to understand and communicate Scripture. No one course gives all needed skills or knowledge; they strategically work together to build exegetical and communicative skills and fill in essential theology. Our trainees are thereby “equipped to preach or teach any part of God’s word accurately and relevantly” and to “equip others to do likewise,” fulfilling our vision as presented in §2.1.

6.2. The Scope and Sequence of Content

The chart below displays our 9-course curricular content in sequence:

|

Foundational Orientation |

Course 1 – Knowing God, Scripture, and Ourselves Course 2 – Knowing the Bible’s Story |

|

Understanding and Communicating Scripture |

Course 3 – Genesis–Exodus: Understanding and Communicating (U&C) Narrative and Law Course 4 – Mark: U&C Gospels Course 5 – Psalms: U&C Poetry Course 6 – Ephesians: U&C Letters Course 7 – Isaiah: U&C Prophecy Course 8 – Revelation: U&C Apocalypse |

|

Applications |

Course 9 – Doing the Ministry of the Word |

Courses 1–2 provide foundation and orientation. They offer our trainees an initial experience of theological study that orients them toward expositional study and communication of Scripture in a manner that is relational, life-situational, and narratival (redemptive-historical). This is particularly helpful since they are adults and (mostly) oral-preference learners (see §4 above).

Course 1 orients them relationally to God in his character and nature, to Scripture as God’s unified Word inspired through diverse human authors, styles, and situations, and to their own role as humble stewards of the authority of God’s Word. Course 2 focuses on the unifying flow of Scripture and how each part uniquely contributes to reveal God’s plan of reconciliation in Christ. Such an initiation to theological studies helps participants stay oriented as they then turn to focus on how to understand and communicate Scripture’s diverse parts in Courses 3–8.

Courses 3–8 cover Scripture’s major genres. This scope is necessary, for our vision is for our trainees to be able to preach or teach a basic expository message from any part of the Bible. The sequence of these six courses has numerous benefits. Alternating OT and NT courses keeps the trainees constantly in both testaments. Courses 3 and 4 also treat the foundational texts of each testament before seeing how the other biblical literature (in Courses 5–8) builds on them. Also, in light of how we distribute communicative skills (see §6.3 below), this course sequence means trainees preach/teach and evaluate entire expository sermons/lessons in both OT and NT.

Course 9 focuses on using the orientation, skills, and knowledge from Courses 1–8 in a variety of ways: e.g., preaching, teaching in diverse contexts, discipling others, and passing on this training to other leaders as in 2 Tim. 2:2. Though Course 9 does not walk through 2 Timothy in the manner of the previous genre-specific courses, it uses 2 Timothy to explore the richness of God’s Word-ministry.

6.3. The Sequence of Communicative Skills

Each course targets the development of a certain smaller communicative skill—sometimes called “speaking sub-skills” or “microskills.”[40] The accumulation of these microskills enables effective preaching and teaching (educational goal 4) and training of others (educational goal 5). For each of our nine courses, there is a communicative task to be accomplished within the course and two communicative tasks to be assigned for the intervening months.

Within Course 1, trainees describe and discuss a theological point from a text they are given about God, Scripture, or their own role. In Course 2, they summarize in their own words the Bible’s overall point, the unique contribution of a major part of the Bible, and the relevance of these insights. In Course 3, they summarize in their own words a passage’s main point, its contribution to the book it is in, and its relevance. In Course 4, they structure a talk and explain why it is faithful to a given text. In Course 5, they use textual evidence to defend the main point of a given passage and critique a wrong idea of it. In Course 6, they articulate applications of a passage’s main point into diverse realms (e.g. personal, marriage, counseling, church, society) and defend why the applications are each legitimate. (This task includes guidance and practice in analyzing their own context.) In each of these tasks, loving and constructive criticism is demonstrated, taught, and practiced. This builds critical engagement into the fabric of the class’s culture from the beginning and will serve their engagement with expositional sermons and lessons in Courses 7–8.

At the end of Course 6, trainees are each assigned a passage from Isaiah from which to construct a sermon or lesson that they will deliver in Course 7. They must provide a detailed plan for their sermon that is fuller than their subsequent fifteen-minute sermonette will be. Trainee plans will be distributed to each trainee in Course 7 so they can see “what is behind” the sermonette. In Course 7, then, they each deliver a whole expository sermon or Bible study lesson (from Isaiah) and constructively critique each other’s. The process is repeated in preparation for and then during Course 8, this time from Revelation.

In Course 9, trainees guide a discussion of a text’s main point and applications within diverse forms of Word-ministry (e.g., small group Bible study, discipleship conversation, counseling). This is the final communicative microskill. It trains them beyond preaching/teaching (lecturing), equipping them to reduplicate and thereby multiply their training with other faithful people.

At the end of each course, each trainee specifies a person (by name) whom they will guide through the course they just finished. In the intervening months before the next course, they must follow through with the resources provided (see §7 below). TLI’s national partners—the indigenous leaders of each cohort on the ground—help strategize and oversee a culturally-appropriate accountability system.

This 9-course scope and sequence is the curriculum. It includes biblical and theological content and exegetical and communicative skills. It is the racecourse sensitively plotted out for our diverse trainees to run in their diverse contexts. By God’s grace, through this curriculum our diverse trainers will help our trainees meet all five educational goals and embody TLI’s global vision. Before exploring the evaluation of this curriculum and an action plan for producing and implementing it, one necessity remains: resources that are educationally and culturally sensitive.

7. Resources in our Curriculum: For Trainers and For Trainees

In light of all that has preceded, we are now in a position to specify effective curricular resources to equip our participants. Some of these resources equip our trainers to guide the trainees’ learning. Some of these resources help our trainees to run their race of learning.[41]

7.1. Resources for Trainers

The resources for our trainers outlined here will enable them to attain the first half of our vision (§2.1), which is:

trainers who, through easy-to-use resources for TLI’s non-formal training environment, are equipped to guide untrained pastors and leaders around the world in face-to-face learning with cultural and educational sensitivity.

Our trainers need (1) a curriculum document that includes our clear vision, our overall curricular goals, the individual course goals that clearly align with and contribute to the curricular goals, and specifications of essential content and skills. As well as this macro-level resource, for each course they need (2) a course syllabus, which includes the course description, learning objectives, course logic, lesson schedule, assignment brief, and course-specific skills and knowledge.

Because our trainers have a wide range of experience and abilities in teaching (see §3.2 above), some need more guidance than others in constructing and delivering a successful TLI course. All, however, need clear and non-negotiable boundaries which ensure that the course, however exactly it is delivered, will contribute what it is supposed to deliver within our curriculum. Therefore, within each course we produce (3) “Lesson Essentials.” Beyond the essentials, most of our trainers are best equipped to provide educationally and culturally sensitive face-to-face learning if they have sample lessons that can be used in whole, in part, or merely as a stimulus. Thus, we provide (4) a Guide for Lesson Plans for each course, which includes structure, content, examples of relevant passages of Scripture, ideas for exercises that could be engaging and appropriate, and comments about cultural issues associated with concrete teaching ideas.[42]

In addition to these four curricular resources, our trainers benefit from the following resources that overlap with but are outside the immediate scope of our curriculum developers: (5) travel and culture documents, both general and location-specific; (6) video training, including introductions to educational and cultural elements noted above (§4 and §5); (6) ongoing consultation with their team leaders, their location’s site directors, and external specialists (e.g., on orality); and (7) certification for our team leaders in each course and in key elements that cut across the curriculum.

7.2. Resources for Trainees

As previously discussed, the majority of our trainees are oral-preference learners to some extent (see §3.2 above). Therefore, the primary resource that will best help our trainees in their initial experience of theological education is this: (1) trainers who are well-equipped to guide educationally and culturally sensitive face-to-face learning environments (see §7.1 above).[43]

Additional resources are also helpful. The trainees will benefit from (2) a translated syllabus for each course. This will help them know where the course is moving, why, and what is expected of them. They will also benefit from (3) a basic coursebook for each course (translated), perhaps 20 pages in length and including understandable and memorable words and phrases, associated images or icons, white space for notes, and room for extra paper. This is given at the beginning of each week-long course.

Each trainee is also expected to train others in the course before the subsequent course. Resources to do this are provided, and these parallel the resources for trainers mentioned above (§7.1). They receive (4) “Lesson Essentials” (translated), which provide the clear snapshots of what each lesson is supposed to do, how, and why. And we provide (5) a Guide for Lesson Plans for each course (translated). They are as described above (§7.1), though modified with culturally transferable qualities of the coursebooks described above (resource 3). While resources 1, 2, and 3 are provided at the beginning of the week-long course, 4 and 5 are given and explained at its end.

These resources for our trainees enable them to attain the second half of our vision (see §2.1 above), which is:

formerly untrained pastors and leaders around the world who, through the Bible, humble confidence in God and his Word, and foundational skills and knowledge, are equipped to preach or teach any part of God’s Word accurately and relevantly and to equip others to do likewise.

8. Evaluation of Our Curriculum

We must evaluate whether and how well the trainees are reaching our curricular goals. This evaluation belongs during the program of courses, in relation to the concrete learning objectives set for each course, and after the completion of the entire program. Such evaluation must include, at the very least, the following categories:

- Evaluation of trainees. The data for evaluation includes self-evaluation by the trainees, evaluation of trainees by the national partner, and evaluation of the trainees by the trainers. Input from national partners is essential for gathering and analyzing data appropriately.

- Evaluation of trainers. This is most robust if it includes self-evaluation by the trainers, evaluation of the trainers by the trainees, and peer-evaluation[44] (if co-teaching) and/or top-down evaluation (i.e., from the trip leader).[45]

- Evaluation of individual courses. This includes evaluation by trainers and trainees of the course flow and content, deliverability, understandability, and resources for trainers and trainees.

- Evaluation of overall curricular scope, sequence, and resources. This includes insights from the curriculum team, trainers (especially team leaders), site directors, national partners, and trainees.

Each of these aspects of evaluation must include a method of in-process evaluation and hindsight, reflective evaluation. The latter must take place over both short-term and long-term periods. Each aspect of evaluation must also ask these three essential questions: (1) Is the goal being met? (This is a pass/fail question.) (2) How well is the goal being met? (This is a question of grade.) (3) What specifics can be changed to be more effective?

9. Action Plan for Moving Forward in Our Curriculum

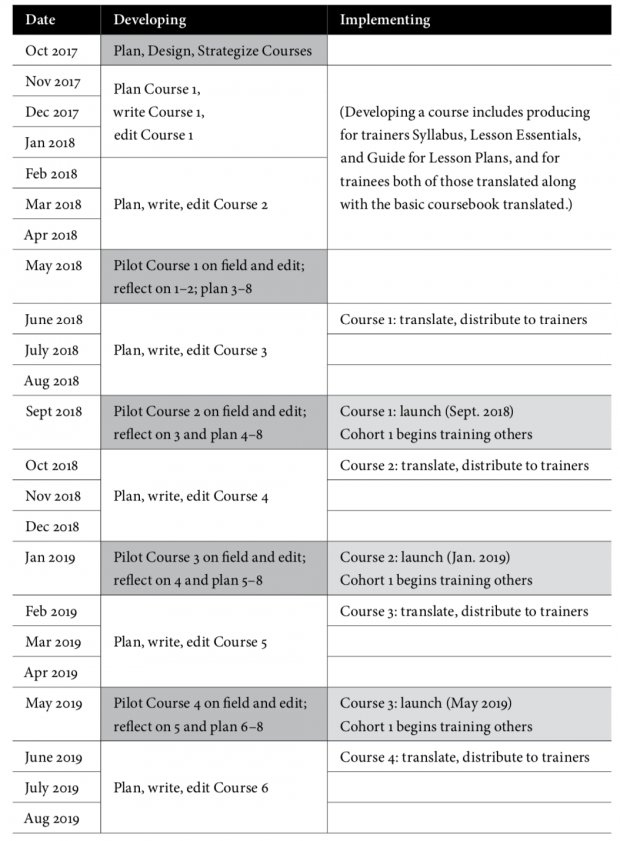

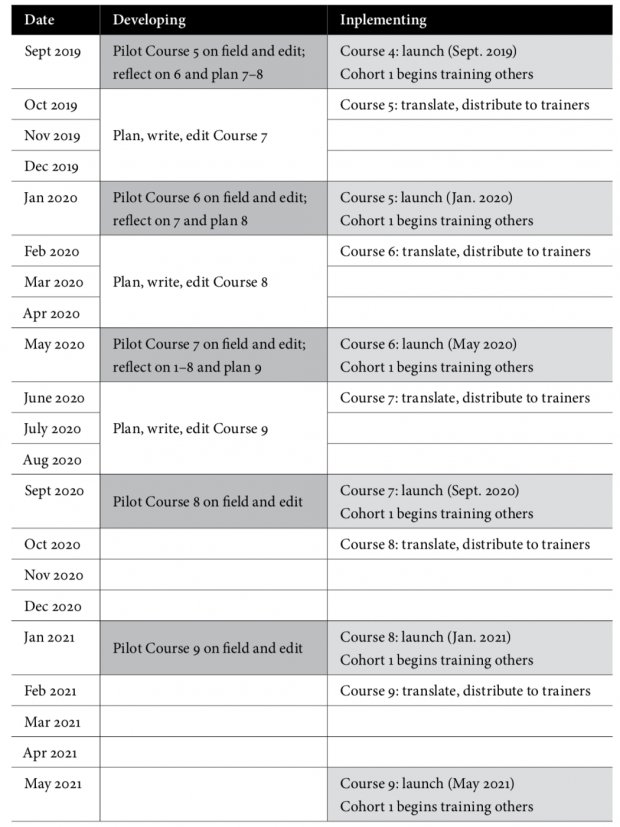

With all curricular elements targeted, explored, and set, we need an action plan for developing and implementing the curriculum. The chart below is peculiar to our setting. It can, however, be more widely instructive and stimulating. Following the presentation of this chart, we will highlight a few governing principles.

A few governing principles must be highlighted. First, we do not want to create a situation where a course must be developed and immediately set in use. Thus, we develop three courses before Course 1 is launched. Second, three months is a realistic timeframe for designing and developing a single course in light of our curriculum staff. This must be taken into consideration. Third, we do not want to launch a course without setting aside time for reflection, field experimentation and discussion with trainers, and editing in light of field use. Then we will be ready to launch a course.

10. Conclusion

The development of our curriculum for non-formal theological training began with TLI’s double-edged vision “to establish and strengthen local churches and their leaders around the world.” We set our own vision for trainees and trainers within this. In light of our vision, we established associated concrete and measurable educational goals toward which we strive, and guide our trainees to strive (§2).

After clarifying our vision and educational goals, we sharpened and specified the diverse nature and needs of the participants in our curriculum, both the trainees and trainers (§3). The qualities characteristic of each set of participants proved crucial for our development of what we offer, how we offer it, and how we provide meaningful resources. Our planning was sharpened still further by attending to various educational and cultural issues inherent in our trainees’ contexts (§4). Practical suggestions and strategies for curriculum design and delivery began to surface, as did a call for us to more deeply engage the educational and cultural issues (§4). We then made explicit three major educational principles that underpin the curriculum’s content and method (§5). This enables our hidden curriculum to be intentionally aligned with and supportive of our explicit curriculum.

In light of all these considerations, we outlined the scope and sequence of our 9-course curriculum. This included the courses’ associated exegetical skills, theological content, and communicative skills (§6). We then highlighted effective resources for our trainers and trainees (§7), resources directly connected to the scope and sequence (§6), but flavored by the educational and cultural explorations of §§3–5 and pointed directly at our double-edged vision (§2).

As we evaluate our design and delivery and the trainees’ and trainers’ growth (§8), and as we work out our concrete and manageable action plan for developing and implementing our course material (§9), the likelihood of attaining our vision increases. By God’s grace and power, we have the joy of helping the indigenous pastors and other Christian leaders around the world reach the five educational goals and thereby be more equipped in the ministry of God’s Word. And they, along with the trainers, will realize the double-edged vision for strengthening the global church.

[1] See Shao-Wen Su, “The Various Concepts of Curriculum and the Factors Involved in Curricula-making,” Journal of Language Teaching and Research 3, no. 1 (Jan 2012): 153–58. Cf. J. Wiles, Leading Curriculum Development (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2009), 2.

[2] Historically, the “curriculum” word group in Latin had to do with “running” (verb: currere) and the “course” on which a race was run (noun: curriculum). The active idea of running a race and the static idea of the racecourse itself are both still helpful for understanding education (contra P. Slattery, Curriculum Development in the Postmodern Era (New York: Garland, 1995), 56; M. Schwartz, “For whom do we write the curriculum?”, Journal of Curriculum Studies (2006): 1–9, both of whom favor the active notion only).

[3] These were stimulated by and expanded beyond the helpful 5-S principle in L. Ford, A Curriculum Design Manual for Theological Education: A Learning Outcomes Focus (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2002), 50–52.

[4] United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) defines “Non-Formal Education” (NFE) as “a structured and sustained body of educational activities that takes place outside of formal education.” See M. Ahmed, The State and Development of Adult Learning and Education in Asia and the Pacific: Regional Synthesis Report (Hamburg: UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, 2009), 7.

[5] Training Leaders International, accessed December 20, 2017, https://trainingleadersinternational.org/about/what-we-do.

[6] See the helpful distinction between “curriculum users” and “curriculum receivers” in Schwartz, “For whom do we write the curriculum?”, 1–2.

[7] B. Ott, Understanding and Developing Theological Education, trans. T. Keefer (Cumbria: Langham Global Library, 2016), 297.

[8] According to a significant amount of literature on cross-cultural theological education, the specific details of the “whom” affect what subjects we deem most appropriate and the order in which we cover them, not to mention the methods in which we deliver them. See the ICETE (International Council for Evangelical Theological Education) Manifesto on the Renewal of Evangelical Theological Education (accessible in Ott, Understanding and Developing Theological Education, 24–31, quote from 26). See chapter 2 of Ott for further argument and literature on this issue.

[9] See M. Knowles, E. Holton III, and R. Swanson, The Adult Learner, 6th ed. (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2005).

[10] E. Lindeman, who is considered the father of andragogy, contrasts andragogy and pedagogy in many ways no longer seen as valid, but his insights about the power of student-centered learning for adults are still worthwhile: E. Lindeman, The Meaning of Adult Education (New York: New Republic, 1926), 8–11. Cf. Ott, Understanding and Developing Theological Education, 111–12; Knowles, Holton, and Swanson, The Adult Learner, 7th ed., 38–39; S. Hoke and B. Taylor, Global Mission Handbook: A Guide for Cross-Cultural Service (Downers Grove: IVP, 2009), 138.

[11] Our approach is known as top-down design, in which a design team and/or teachers set the course of learning rather than the students setting their own (known as bottom-up curricular design). Our top-down design method is still importantly learner-centered. The andragogic literature that equates andragogy with bottom-up design has faulty foundations. First, the effectiveness of bottom-up over top-down design is questioned on empirical grounds: see S. Rosenblum and G. Darkenwald, “Effects of Adult Learner Participation in Course Planning on Achievement,” Adult Educational Quarterly 22, no. 3 (1983): 147–60; cf. S. Merriam and R. Caffarella, Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, 1999), 90–91. Second, the equation of andragogy with bottom-up curriculum design is especially criticized on cultural grounds. Bottom-up design is likely too Western to help us in our context(s). Many andragogic suggestions are based on psychological and educational research done primarily among the WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) community, who make up only 25% of the world’s population. See A. Tulloch, “Adult Learning across Cultures,” Neuroanthropology (blog), May 30, 2014, accessed April 19, 2017, http://blogs.plos.org/neuroanthropology/2014/05/30/adult-learning-across-cultures/; T. Hatcher, “Towards Culturally Appropriate Adult Education Methodologies for Bible Translators: Comparing Central Asian and Western Educational Practices,” Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics 2, no. 3 (2008): Appendix 3, http://www.gial.edu/documents/gialens/Vol2-3/Hatcher-Adult-Ed-Methodologies.pdf. G. Hofstede and G. J. Hofstede observe that “traditional psychology” itself “is a product of Western thinking, caught in individualist assumptions” in Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (London: McGraw-Hill, 2005), 108; S. Merriam, R. Caffarella, and L. Baumgartner write that “the knowledge base that has developed around learning and adult learning has been shaped by what counts as knowledge in a Western paradigm” in Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide, 3rd ed. (San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, 2007), 217. Indeed, a strong influence in much of Western educational theory is Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs” in which “self-actualization” is the pinnacle. Hofstede and Hofstede counter that self-actualization “can only be the supreme motivation in an individualistic society. In a collectivist culture, what will be actualized is the interest and honor of the in-group, which may very well ask for self-effacement from many of the in-group members. Harmony and consensus are more attractive ultimate goals for such societies than individual self-actualization” in Cultures and Organizations, 108. Cf. R. Tucker and S. Ang, “The Academic Acclimatisation Difficulties of International Students of the Built Environment,” Emirates Journal for Engineering Research 2, no. 1 (2007): 1–9.

[12] Ott, Understanding and Developing Theological Education, 112. Cf. Knowles, Holton, and Swanson, The Adult Learner, 7th ed., 38–39.

[13] See another example of a similar shift in Knowles, Holton, and Swanson, The Adult Learner, 6th ed., 68.

[14] Ott, Understanding and Developing Theological Education, 112.

[15] T. Ward, “The Split-Rail Fence: An Analogy for the Education of Professionals,” Learning Systems Institute report (East Lansing: Learning Systems Institute and Human Learning Research Institute of Michigan State University, 1969), 64. Cf. S. Burton, Disciple Mentoring: Theological Education by Extension (Pasadena: William Carey Library, 2000), chapter 5.

[16] Merriam, Caffarella, and Baumgartner, Learning in Adulthood, 227–38.

[17] Ibid., 238.

[18] Ibid., 188.

[19] Ibid., 238. Cf. T. Fosokun, A. Katahoire, and A. Oduaran, The Psychology of Adult Learning in Africa (Hamburg: UNESCO Institute for Education and Pearson Education South Africa, 2005), 36.

[20] P. Hiebert, R. D. Shaw, T. Tiénou, Understanding Folk Religion: A Christian Response to Popular Beliefs and Practices (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1999). Cf. T. Steffan, “Storytelling,” in Evangelical Dictionary of World Missions, ed. A. S. Moreau (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2000), 909.

[21] See “The Learning Curve 2013,” The Economist Intelligence Unit (explore http://thelearningcurve.pearson.com/). Cf. H. Wursten and C. Jacobs, “The Impact of Culture on Education: Can We Introduce Best Practices in Education across Countries?” accessed April 20, 2017, https://geert-hofstede.com/tl_files/images/site/social/Culture%20and%20education.pdf. See T. Hatcher’s helpful counter to Steffan’s comments about storytelling as universally transferable: Hatcher, “Towards Culturally Appropriate Adult Education,” Appendix 3.

[22] G. De Vita, “Learning Styles, Culture and Inclusive Instruction in the Multicultural Classroom: A Business and Management Perspective,” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 38, no. 2 (2001): 165–74, 167; quoting A. Grasha, “Using Traditional Versus Naturalistic Approaches to Assessing Learning Styles in College Teaching,” Journal of Excellence in College Teaching 1 (1990): 23–38, 26.

[23] De Vita, “Learning Styles,” 167 (see 165–74). Cf. D. Pratt, “Conceptions of Self within China and the United States: Contrasting Foundations for Adult Development,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 15, no. 3 (1991): 285–310; Tucker and Ang, “Academic Acclimatisation Difficulties,” 1–9; S. Charkins, D. O’Toole, and J. Wetzel, “Linking Teacher and Student Learning Styles with Student Achievement and Attitudes,” The Journal of Economic Education 16, no. 2 (1985): 111–20; Y. Yamazaki, “Learning Styles and Typologies of Cultural Differences: A Theoretical and Empirical Comparison,” International Journal of International Relations 29, no. 5 (Sept 2005): 521–48.

[24] See E. T. Hall, Beyond Culture (New York: Anchor, 1981). C. B. Halverson and S. A. Tirmizi, eds., Effective Multicultural Teams: Theory and Practice (Netherlands: Springer, 2008); C. B. Halverson, “Cultural-Context Inventory: The Effects of Culture on Behavior and Work Style” in 1993 Annual: Developing Human Resources, ed. J. W. Pfeiffer (San Diego: Pfeiffer and Company, 1993). For a popular-level summary, see B. Neese, “Intercultural Communication: High- and Low-Context Cultures,” Southeastern University Online Learning (Aug 2016), http://online.seu.edu/high-and-low-context-cultures/.

[25] See J. Georges, “From Shame to Honor: A Theological Reading of Romans for Honor-Shame Contexts,” Missiology 38, no. 3 (2010): 295–307. Cf. J. Georges, The 3D Gospel: Ministry in Guilt, Shame and Fear Cultures (Timê Press, 2016). For one example of the complexity of this scheme, see R. Nisbett and D. Cohen, Culture of Honor: The Psychology of Violence in the South (Boulder: Westview Press, 1996) for an exploration of how a deeply-rooted shame culture among Whites in the South plays a significant role in the higher rate of violent crimes among southern Whites than other Whites in the US. Likewise, Y. Wong and J. Tsai show that in collectivist cultures the notions of shame and guilt can be less pronounced, and among the Swahili people in Mombasa (at least) the sense of communal shame is more closely associated with their actions than their being, which blurs the lines between guilt and shame in typical definitions: Y. Wong and J. Tsai, “Cultural Models of Shame and Guilt,” in Handbook of Self-Conscious Emotions, eds. J. Tracy, R. Robins, and J. Tangney (New York: Guilford Press, 2007): 210–223, see especially 212–13. Biblical scholars are increasingly aware of the power of honor–shame dynamics in the cultures represented in Scripture, but this has not transferred well enough to many teachers in TEE (Theological Education by Extension); e.g., D. deSilva, Honor, Patronage, Kinship and Purity: Unlocking New Testament Culture (Downers Grove: IVP, 2000), 25; cf. R. Rabichev, “The Mediterranean Concepts of Honour and Shame as Seen in the Depiction of the Biblical Women,” Religion and Theology 3, no. 1 (1996): 51–63; R. F. Kensky, “Virginity in the Bible,” in Gender and Law in the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East, ed. V. H. Matthews, B. M. Levinson, and T. Frymer-Kensky (Sheffield: JSOTSup, 1998): 79–96.

[26] See the website dedicated to the work of Geert Hofstede and Gert Jan Hofstede, accessed at https://geert-hofstede.com/national-culture.html. See also Hofstede and Hofstede, Cultures and Organizations. Cf. A. Tamas, “Geert Hofstede’s Dimensions of Culture and Edward T. Hall’s Time Orientations,” http://www.tamas.com/sites/default/files/Hofstede_Hall.pdf.

[27] See E. Hall, Hidden Differences: Doing Business with the Japanese (Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1987); G. Ko and J. W. Gentry, “The Development of Time Orientation Measures for Use in Cross-Cultural Research,” in Advances in Consumer Research, vol. 18, eds. R. H. Holman and M. R. Solomon (Provo: Association for Consumer Research, 1991), 135–142. Cf. A. Tamas, “Geert Hofstede’s Dimensions of Culture and Edward T. Hall’s Time Orientations,” http://www.tamas.com/sites/default/files/Hofstede_Hall.pdf.

[28] Lausanne Movement, “Orality,” accessed December 22, 2017, https://www.lausanne.org/networks/issues/orality.

[29] M. D. Sills, Hearts, Heads, and Hands: A Manual for Teaching Others to Teach Others (Nashville: B&H, 2016), 7. Cf. M. D. Sills, “Primary Oral Learners: How Shall They Hear?” (chapter 9) in Reaching and Teaching: A Call to Great Commission Obedience (Chicago: Moody, 2010) and M. D. Sills, “Reaching Oral Learners” (chapter 5) in Changing World, Unchanging Mission: Responding to Global Challenges (Downers Grove: InterVersity, 2015).

[30] W. Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (London: Routledge, 2002).

[31] R. Arnett, “Discipleship in the Face of Orality,” Orality Journal 6, no. 1 (2017): 49–58, 49–50.

[32] Arnett, “Discipleship,” 51.

[33] H. Klem traces significant social damage that has been caused by insensitively introducing literacy into largely oral cultures in Oral Communication of the Scripture: Insights from African Oral Art (Pasadena: William Carey Library, 1982).

[34] S. E. Jones, “Reflections on the Lecture: Outmoded Medium or Instrument of Inspiration?” Journal of Further and Higher Education 31, no. 4 (2007): 397–406. Cf. D. Bligh, What’s the Use of Lectures? (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000); P. Race, The Lecturer’s Tool Kit: A Practical Guide to Learning, Teaching & Assessment, 2nd ed. (Abingdon: Routledge Falmer, 2001). Even though we do not use PowerPoint on the field, insights from education literature on the limits of PowerPoint in helping students acquire skills are transferrable regarding the sole use of lecture in our contexts: see J. E. Susskind, “Limits of PowerPoint’s Power: Enhancing Students’ Self-Efficacy and Attitudes but Not Their Behavior,” Computers & Education 50, no. 4 (2008): 1228–39.

[35] P. Shaw, Transforming Theological Education: A Practical Handbook for Integrative Learning (Cumbria: Langham Global Library, 2014), 79; see 81–88.

[36] Ibid., 81.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Susskind, “Limits of PowerPoint’s Power,” 1228–39. See also the work on practice and the experience of success in the acquisition of skills in G. C. Wolniak, M. J. Mayhew, and M. E. Engberg, “Learning’s Weak Link to Persistence,” The Journal of Higher Education 83, no. 6 (2012): 795–823; J. Perrin, “Features of Engaging and Empowering Experiential Learning Programs for College Students,” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 11, no. 2 (2014): article 2; W. J. McKeachie, “Good Teaching Makes a Difference – and We Know What It Is,” in The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: An Evidence-Based Perspective, ed. R. P. Perry and J. C. Smart (Dordrecht: Springer, 2007), 457–74, 471.

[39] The word “full” is important.

[40] What follows has been inspired by but developed differently than the work of H. D. Brown, Teaching by Principles: An Interactive Approach to Language Pedagogy, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: Pearson ESL, 2000), chapter 17: “Teaching Speaking.” For a similar general approach and examples of practical ways to develop speaking sub-skills, see the booklet: K. Lackman, “Teaching Speaking Sub-skills: Activities for Improving Speaking,” accessed December 22, 2017, http://www.kenlackman.com/files/speakingsubskillshandout13poland_2_.pdf.

[41] The approach of equipping the curriculum user (trainer) and the curriculum receiver (trainee) is often used, though it has pitfalls. The entire approach is critiqued in Schwartz, “For whom do we write the curriculum?”, 2–4 and D. Anderson, “Educational Eldorado: the claim to have produced a practical curriculum text”, Journal of Curriculum Studies 15.1 (1983): 5–16, though in our opinion their critiques should be given weight as helpful stimuli for avoiding pitfalls rather than for abandoning the approach altogether.

[42] E. W. Eisner believes that “good curriculum materials both emancipate and educate teachers” (“Creative curriculum development and practice”, Journal of Curriculum and Supervision 6.1 (1990): 62–73), though A. Shkedi demonstrates how the teachers themselves rarely consider successful a single curriculum document that contains attempts to both educate and emancipate them (“Can the Curriculum Guide Both Emancipate and Educate Teachers?”, Curriculum Inquiry 28 (1998): 209–29). We use different documents within a whole packet so as to keep separate these diverse goals of our curricular material.

[43] According to Schwartz, “The task of writing curriculum needs a new approach. It should not be written for the student, because students vary from class-to-class. It should not be written in a way that attempts to address every practical situation—because there are just too many of these. The focus of curriculum-writing should be shifted away from directing the students, and towards engaging, and even educating, teachers” (“For whom do we write the curriculum?”, 4). In essence, this is the approach we have laid out above. The best resource for the student is the teacher, and thus most of our curricular material is geared toward equipping (even educating) the teacher. That said, this does not mean we cannot provide resources to the students directly. Indeed, because part of our vision for our trainees is for them to then train others, our trainees become trainers and should be equipped as such.

[44] Cf. D. Gosling, Peer Observation of Teaching: Implementing a Peer Observation of Teaching Scheme with Five Case Studies (London: Staff and Educational Development Association, 2005); E. Piggot-Irvine, “Appraisal Training Focused on What Really Matters,” International Journal of Educational Management 17, no. 6 (2003): 254–61; J. Byrne, H. Brown, and D. Challen, “Peer Development as an Alternative to Peer Observation: A Tool to Enhance Professional Development,” International Journal for Academic Development 15, no. 3 (2010): 215–28.

[45] On the “inspectorial” or “evaluation” model, see P. Race, Making Learning Happen: A Guide for Post-Compulsory Education, 2nd ed. (London: SAGE, 2010), 221.