1. Introduction

The exorcism stories are not simply awe-inspiring, isolated events in Mark. Demonic encounters in the Second Gospel are like the bricks of a house: Together, they construct a story grander than any one of these accounts does on its own. This article lifts the eyes of the reader to see the story of Mark, with a focus on not only the details but also the structure of the Gospel as a whole.

We will explore the following elements of Mark’s Gospel. First, we will examine the Prologue of Mark (1:1–15) as an important organizing element. God the Father affirms Jesus as the Beloved Son and the Son is the Spirit-bearer whose first act in ministry is to cast out a demon. Second, the distribution of these exorcisms throughout Mark is another important organizing element of the Gospel. His placement of these stories within the whole book substantiates Mark’s emphasis on Jesus as both the authoritative Son and suffering servant (Mark 10:42–45). By examining how Mark’s Gospel presents Jesus and his ministry of exorcism, this article seeks to encourage believers around the world to view exorcisms Christologically, but not vice versa.

2. Mark’s Prologue (1:1–15)

Ancient works like the Gospel of Mark often use introductions programmatically; that is, they function to summarize a person’s identity and actions.[1] The opening section of Mark’s Gospel is no different.

Three observations from Mark 1:1–15 are important for understanding the exorcism accounts. First, Mark appears to be concerned with establishing the nature of Jesus through his works and with the words spoken about him. Mark begins by addressing the nature of Jesus:

- “Lord” (1:3)

- “one more powerful than I” (1:7)

- “You are my beloved Son with whom I’m well pleased” (1:11)

However, he also gives ample time to the actions and ministry of Jesus

- “He will baptize with the Holy Spirit” (1:8)

- “The Spirit cast him out into the wilderness” (1:12)

- “Jesus went into Galilee proclaiming the good news of the kingdom of God” (1:14)

Mark was concerned with Jesus’s identity and what had been spoken about him.

Directly following the Prologue, Mark tells of Jesus’s exorcism at the Capernaum Synagogue. The prominence of this exorcism account and its proximity to the Prologue suggest that Jesus’s identity and his confrontation with the spirit world are closely linked.[2] The exorcism accounts repeatedly communicate who Jesus is over the course of the Gospel. Mark 1:24 records the words of the unclean spirit: “I know who you are—the Holy One of God!” And Mark 3:11 records the demonic refrain: “You are the Son of God!”

These passages echo the words given in three key “eschatological moments” or “pillars” of Mark’s Gospel that describe Jesus as God’s Son (1:11; 9:7; 15:39). By illustrating Jesus’s power to act and frequently emphasizing Jesus’s status as the “Holy One” and “Son” of God, the exorcism stories make Jesus’s identity known both in word and action.

Mark also speaks about the two baptisms of Jesus: One was executed by him and the other was executed on him. Mark records the baptism that Jesus will use to minister to others: “He will baptize with the Holy Spirit” (1:8). Jesus wields the spirit in his ministry just as he receives the spirit at his baptism. This contrast between John’s and Jesus’s baptisms establishes the distinctly Spiritual nature of Jesus’s ministry. Jesus’s exorcisms are to be understood as more than isolated acts of philanthropy. Rather, Jesus’s entire life and ministry are to be seen as “an attack upon these evil powers.”[3]

The tension between Jesus and Satan unfolds throughout the first half of Mark’s Gospel. Their duel in the desert (1:12–13) marks the beginning of Jesus’s campaign against the “house” of Satan. While Matthew and Luke show how Jesus resisted Satan’s temptations, the hearer of Mark’s Gospel is told only that Jesus was tempted by Satan and then ministered to by angels; the passage includes nothing about who “won” or what the outcome was. The only active verbs in these two verses apply to the Spirit’s action of “casting out” Jesus to meet Satan and the angels’ actions of “serving” Jesus. The pericope, leaving out major details, “neatly arranges them in two camps: on the one side… Jesus… on the other, Satan… [with] no indication of outcome.”[4]

Mark’s reluctance to resolve this interaction leaves his audience wondering when such a resolution will occur. This conflict develops throughout the remainder of Mark.[5] Jesus is imbued with the Spirit of God and is thereby thrust into a conflict with Satan (i.e., 1:12). This battle is carried out most vividly in the exorcism accounts where Jesus plunders the house of “the strong man” (3:27).

The above observations about Mark’s Prologue demonstrate his desire to illustrate Jesus’s divine identity by forecasting what Jesus will do and recounting what others had said about him (namely, John and the voice from heaven). The Gospel also intends to teach the audience of the profoundly Spiritual nature of Jesus’s ministry and show that his life and ministry would confront the forces of Satan (a conflict waged in 1:12–13). That is, the exorcism accounts are evidence of the Spiritual dimension of his ministry, which is fundamentally a war on evil.

In sum, Mark’s Prologue is constructed of two parts. First, it establishes Jesus’s divine identity, and then, it sets up Jesus’s full-scale Spiritual attack on the Kingdom of Satan. In these few verses, the author’s attention to Jesus’s identity, work, and baptisms, as well as the temptation of Satan, all support the notion that Jesus’s divine lineage is crucial to Mark. It also shows that this section was intended to be the seedbed for the cosmic battle between Satan and Jesus, which would grow through the exorcism stories and culminate with the death and resurrection of Jesus.

3. The Three “Pillars” of Mark’s Gospel

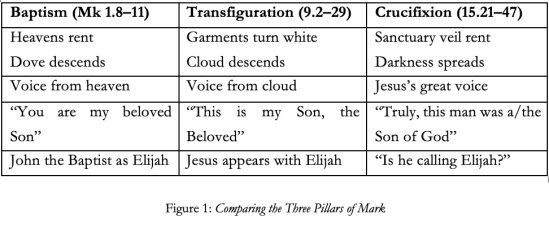

Commentators generally divide the body of the Gospel of Mark into three sections: 1:14 (or 16)–8:21 (or 27), 8:21 (or 27)–10:45 (or 11:1), and 10:45 (or 11:1)–16:8.[6] Ched Myers adds to the above structural breakdown by organizing the Gospel around three “pillars.”[7] Each of these pillars highlights a defining event that serves to anchor the hearers to the purpose of each respective narrative section, or “pillar.” As Myers writes, “At the level of narrative, each moment is fundamental to the regeneration of the plot,”[8] with all three comprised of four similar elements: a sign in nature, a divine voice, an explanation of Jesus’s identity, and the fulfillment of the Scriptures. For Myers, these three events are apocalyptic turning points in the Gospel:

The above three instances “define” Jesus himself at key moments in the story. Rather than the reactions of Mark’s characters toward Jesus,[9] it is these testimonies of Jesus’s divine sonship that serve as benchmarks that remain central for the hearers. These accounts have more of a normative effect on my exegesis of other passages, namely the exorcism stories.

The first pillar is Jesus’s baptism. After the baptism (1:8–11), the exorcism of Mark 1:21–28 recounts the crowd’s amazement at Jesus’s teaching (1:22) and subsequent exorcism (1:27). Mark’s audience, however, had just heard about the baptism of Jesus in 1:8–11 and God’s pronouncement of him as “my beloved Son in whom I’m well pleased” (1:11). Lacking knowledge of this event, the crowd is astonished as if they had witnessed the performance of a local magician. Mark, however, intends to impart more information on his hearers—that is, he intends for them to perceive the divine sanction in the deeds of Jesus that he recounts. Furthermore, all of the exorcism accounts in Mark occur within the first nine chapters. This suggests that the author, through the organization of the encounters, intends to emphasize the raw authority and power of Jesus as the Beloved Son, a title used during both the baptism and the Transfiguration.

The Transfiguration in Chapter 9, after which Mark records only one more exorcism, is the second pillar.[10] In 9:2–13, Jesus’s appearance changes radically before Peter, James, and John and in the presence of Moses and Elijah. Only a few verses after this event, Mark 9:15–19 begins with the phrase, “And when all the people saw Jesus, they were overwhelmed with wonder and ran to greet him.” In this scene, Jesus had done nothing directly to elicit their amazement. They had not seen the Transfiguration, and yet, they flock to him in amazement. The hearer, knowing what happened in the presence of Peter, James, and John, recognizes this as additional evidence of Jesus’s filial relationship with God, which had been reiterated only eight verses earlier (9:7). Later, in 9:19, Jesus answers a man who comes to him for an exorcism, stating, “You unbelieving generation. How long shall I stay with you? How long shall I put up with you?” Again, the hearer has a unique perspective on this exorcism and Jesus’s statement because of its proximity to the Transfiguration. After witnessing this display of power and Jesus’s position of authority among Moses and Elijah, the hearer can interpret the “faithlessness” of 9:19 specifically as faithlessness in God’s “beloved Son” (Mark 9:7).[11]

The third pillar is the centurion’s confession of Jesus as the Son of God in Chapter 15 and it functions similarly to the other two pillars. In 15:38–39, the centurion’s comment comes as a direct response to seeing the portents accompanying Jesus’s death: “And the curtain of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom. And when the centurion, who stood there in front of Jesus, saw how he died, he said, “Surely this man was the Son of God!” At this point in the Gospel, Mark chooses a Gentile soldier to confess the divine status of Jesus after seeing the events of the death of Jesus. Clearly, the Evangelist is eliciting a certain response from the hearers. If this pagan soldier saw Jesus as the Divine, then it would have been patently obvious.

These three pillars of Mark’s Gospel appear to the audience as apocalyptic, revelatory moments through which they are called to understand the rest of the Gospel and make sense of the words and deeds of Jesus. Any of the hearers of Mark’s Gospel who did not grasp the intended meaning of these revelatory moments would be unsure as to why the author had recounted the life of Jesus (and in this case, the exorcism stories) in the manner he had.

Given that, for Mark’s audience, the above events are “inside information” regarding the identity and significance of Jesus, the events of each exorcism story that reinforce his identity and significance would have been understood with greater clarity than they might otherwise have been. Thus, the demonic cry of “I know who you are—the Holy One of God!” in 1:24 should be seen as a reinforcement of Mark’s theme of Jesus’s divine sonship, not as an arbitrary detail added to the story. Similarly, the propensity of demons to say to Jesus, “You are the Son of God!” (3:11) should be perceived in the same light. In sum, these interactions with demons contribute to Mark’s claims about the identity of Jesus and support the overarching purpose of the narrative.

4. The Pace, Flow, and Distribution of Exorcism Accounts

Throughout Chapter 13, Mark 1:16 offers a “day-to-day” picture of Jesus and his ministry.[12] Jesus is seen moving from town to town while preaching, casting out demons, and more. Not until Chapter 14 does the pace slow significantly. Although Mark composed his Gospel with little attention to chronology, the “slow-motion” account of the last few chapters is notably conspicuous. Mark 14:10–15:47 alone takes place over a period of just 24 hours, approximately.

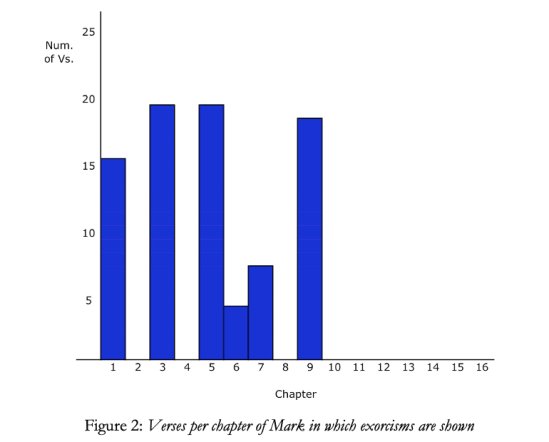

The “flow” of the Gospel refers to the momentum generated by the high volume of elements in a certain section. The exorcism accounts are distributed in an interesting way in the Gospel. The graphs below show that all references to exorcism, demons, and unclean spirits appear in the first nine chapters of Mark. Moreover, over 78% of all the Markan exorcisms occur in the first eight chapters alone.[13]

The above distribution of exorcism stories in Mark begs the question of why the Gospel is “front-loaded” in this manner. What advantage might there be to including all these accounts early in the text and saving none for the last six chapters? Mark 9 is the turning point in Mark’s Gospel and suggests an answer. Mark 9:14–29 is the final exorcism, taking place immediately after the Transfiguration in 9:2–13. These two passages are followed by a significant number of accounts that touch on the theme of humility:

- 9:30–32: Jesus foretells his death and resurrection for the second time (the first is found in Mark 8:31–38).

- 9:33–37: The disciples argue about who is the greatest (where he uses children as an object lesson).

- 10:13–16: Jesus rebukes his disciples, instructing them to let the children come to him.

- 10:32–34: Jesus predicts his death and resurrection for the third time.

- 10:35–45: Jesus deals with the request of the sons of Zebedee to sit by him in the Kingdom, saying, “Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant.”

- 11:1–11: Jesus enters Jerusalem triumphantly, riding into Jerusalem on a donkey.[14]

- 11:18: The chief priests and scribes desire to kill Jesus.

- 12:1–44: In the Parable of the Tenants, the “son” in the story is killed, and the final story is about the widow’s offering.

The theme of humility dominates the last half of Mark, culminating with the death of Jesus. Mark validates Jesus’s authority and greatness as the Son of God in the cosmic battle in the first half of the Gospel (1:9–11, 12–13; 9:2–14) and begins working toward his ultimate expression of Jesus’s authority and greatness with the crucifixion and resurrection. The gap in the Gospel between the end of the exorcism accounts and the beginning of the Passion creates a distance between the Jesus we see as dominant over evil powers and the one who is the servant of all (9:35). Mark’s shift in emphasis helps the audience receive the account of the Passion with the proper perspective on Jesus’s suffering and death.[15]

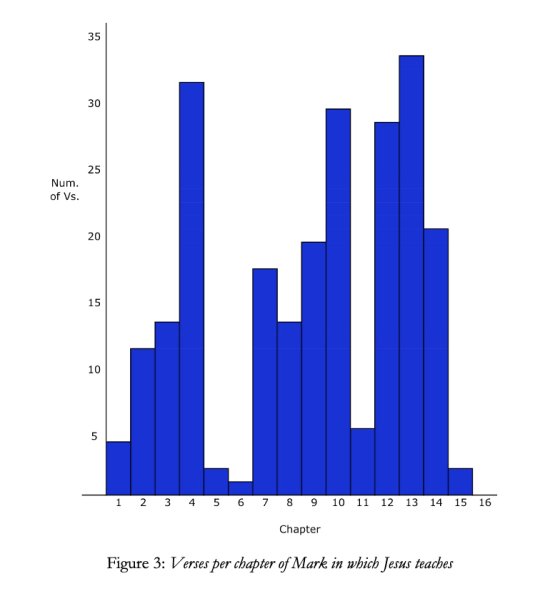

Other statistics regarding the frequency of events and elements in Mark may also be important when compared with Figure 3. Teaching blocks are inversely proportionate to the exorcism accounts in Mark. That is, the teaching sections in Mark increase as the chapters advance[16] in an inverse relation with the exorcism accounts. Approximately 40% of Jesus’s teaching takes place in Chapters 1–8, whereas 60% take place in Chapters 9–16.[17] The graph below clearly illustrates this intensification.

When exorcism is more frequently employed, teachings appear less. Moreover, as the frequency of teachings increases, exorcisms diminish, eventually disappearing altogether. In this context, the following question is important: Why would Mark begin his Gospel with more exorcisms and fewer teachings but then reverse this prioritization as the Gospel reaches its conclusion?

The exorcisms appear to be Mark’s primary method of validating the power and authority of Jesus’s teaching. Mark 1:21–28 demonstrates this point well. In 1:22, the crowds are amazed simply by Jesus’s teaching, which were far superior to those of the scribes. At the end of the pericope in 1:27, the exorcism clearly strengthens the authority of Jesus’s teaching from the perspective of the audience. They repeat their amazement at his teaching, stating, “A new teaching, and with authority!” They then add, “He even orders to impure spirits and they obey him!”

Jesus begins interpreting his own miraculous work by describing it as an assault on the “house” of the strong man (3:22–30). Jesus later interprets other miracles as well (8:19–21; 11:20–25), instructing the disciples on how his forthcoming death and resurrection should be understood (8:31–33; 9:9–13; 9:30–32; 10:32–34; 12:1–12). Jesus’s verbal explanation of the events of the Gospel is crucial for the audience’s comprehension and the exorcism accounts are no exception. Indeed, at the very outset of his ministry, Jesus is found “preaching the gospel of God” (1:14); however, in the beginning, this ministry of teaching is not yet fully developed. Rather, Jesus’s power is first displayed through exorcism and his ministry of teaching continues to grow as the Gospel develops toward its culmination on the cross.

The book of Mark is “front-loaded” with exorcism accounts and “back-loaded” with teaching pericopae. The relationship between these exorcisms and teaching sections should be understood with a wider understanding of how the author structures the plot. Initially, Mark’s aim was to establish Jesus’s authority through signs and wonders—primarily exorcism accounts. His object was to legitimize Jesus’s ministry and teachings through the overt display of power as seen in the exorcisms. Halfway through Chapter 9, the Gospel shifts and begins to prepare the hearer for the humiliation of Jesus on the cross. The exorcism accounts are no longer needed at this point because Jesus’s power has already been validated and the exorcisms depict a Jesus who is more victorious through domination rather than humiliation. The increase in teaching sections functions primarily to interpret events that have already happened and those that will soon occur—all in an effort to demonstrate to the audience that Jesus is the Son of God.

5. Conclusions

In Mark’s Gospel, Jesus is endowed with divine power over the spirit realm. Jesus is God’s emissary who enters the “house of the strong man” to plunder him (3:27). Jesus, as the bearer of the Holy Spirit, initiates a cosmic battle between good and evil while casting out unclean spirits. The battles Jesus wages and wins throughout Mark are a testament to his heavenly origin and demonstrate the purpose for which he has come.

However, Jesus’s own teachings also expound on the implications of his exorcism ministry. Mark 3:23–26 supports the idea that each exorcism is part of a broader campaign against “the strong man” Satan. The theological significance of Jesus’s preaching and its role in expounding his ministry of exorcism help inform one’s reading of the Gospel as a whole.

This brief exploration of exorcism in Mark highlights the need for a thorough evaluation of how exorcism is understood in many Christian communities today. I will now outline two possible implications.

First, the three sections (“pillars”) of Mark contain similar language that focuses the reader’s attention on the purpose of Mark’s account: to turn the reader to Christ. The first pillar is Jesus’s baptism, at which God the Father bestows his own authority on Jesus (1:8–11). Just after the baptism, Jesus begins his public ministry with an exorcism as a display of this authority (1:21–28). Here Jesus fires a “warning shot” in his assault on the Kingdom of Satan, which the demon recognizes (1:24). It is similar to the second and third pillars in Mark: The mighty acts of Jesus (here, exorcism) interpret Jesus and not vice versa. Exorcism is not an end in and of itself; rather, it always serves to exalt Jesus in the life of the local church.

Second, exorcism accounts “front-load” the Gospel, suggesting that the first half of Mark seeks to validate Jesus’s authority and prepare the hearer for his teaching about his humiliation on the cross and his final act of humble crucifixion. In this way, the exorcism accounts have an important but supporting role in relation to other plot events. As significant as the exorcism stories are, they are not the full story of Jesus that Mark intends to communicate. The hearers are supposed to see Jesus as a humble victor who conquers Satan not simply through domination but also through humiliation. Readers of Mark better understand exorcism when keeping it in perspective and not allowing this important ministry to take the focus away from Jesus’s humiliation and the call to follow him humbly (Mark 10:42–45).

The Markan exorcism accounts establish Jesus’s dominance over the spirit realm prior to his death on the cross. Jesus’s purgation of unclean spirits, taken in tandem with his humiliation, shows the reader that the events of the cross were not outside of his control. Rather, the mission begun in the Prologue is completed quite unlike how it begins. The exorcisms of Chapters 1–9 begin Jesus’s assault on the strong man mentioned in Mark 3. After this, the victorious Son of Man “gives his life as a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45). As Matthew tells us, “All authority in heaven and on earth” has been given to Jesus. Indeed, Jesus overthrows Satan and his demons in each exorcism, demonstrating that this sovereign power is becoming manifest even throughout the events of Jesus’s ministry. However, in Mark’s Gospel, Jesus’s act of laying down his own life is also a manifestation of his authority, as he not only conquers Satan himself but also Satan on behalf of the ransomed many. May the global church increasingly reflect on what authority and humility look like together in the Body of our crucified and risen Lord.

[1] Morna Hooker, Gospel According to St. Mark (London: A & C Black, 1997), 55–6.

[2] Hurtado, “Monotheism in the New Testament” (working paper, Edinburgh Research Archives, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, 2009).

[3] Larry Hurtado, Mark. New International Biblical Commentary (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1995), 66.

[4] R. T. France, The Gospel of Mark: A Commentary on the Greek Text, NIGTC (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 83–4. James Robinson adds, “The introduction to Mark has made it clear that Mark speaks in cosmic language of a struggle between the Spirit and Satan” (The Problem of History in Mark, Studies in Biblical Theology [London: SCM Press, 1962], 33).

[5] Cf. Robinson, Problem.

[6] Rikki Watts comprehensively reviewed the opinions of commentators on the structure of Mark and arrived at this conclusion (Isaiah’s New Exodus and Mark, WUNT 2.88 [Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1997], 124).

[7] Ched Myers, Binding the Strong Man: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1995), 390–91.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Here, I am referring to the crowd’s awe-struck reaction (Mark 1:21–28) or the Pharisees’ blasphemous accusation (3:22–30).

[10] The final account is Mark 9:14-29.

[11] Interestingly, Raphael’s Transfiguration und Heilung des Besessenen Knaben (ca. 1520) depicts the events of Mark 9:2–29 with Jesus being transfigured prior to performing an exorcism on a young boy. The painting portrays a crowd seemingly unaware of what is happening on the mountain, and yet it presents the Transfiguration as a lens through which the connoisseur is to understand the impending exorcism.

[12] This is not to imply that the pace of Jesus’s life was normal, only that the author aims to show Jesus in “real-time.”

[13] That is, 78% of exorcisms occur from Mark 1:15–8:26. Only pericopae entirely dedicated to the act (e.g., 1:21–28) or topic (e.g., 3:22–30) of exorcism are considered “exorcism accounts.” Others, in which exorcism is only a part of the whole, are only counted in as many verses relate to exorcism. The Transfiguration and the Resurrection are not counted in this tally.

[14] Although there is some disagreement about whether Jesus’s ride into Jerusalem on a donkey is an act of abasement, in the context of this discussion, Zech 9.9 is understood to be a reference to the humility of the coming Messiah.

[15] Mark may also have discontinued his account of the exorcism stories because he did not want anything to overshadow the events of the Holy Week. In addition to the exorcism accounts, Jesus’s more general miraculous works begin to taper off as well. The healing of Bartimaeus (10:46–52) and the cursing of the fig tree (11:12–13, 20–25) are the only two miracles after Jesus’s exorcism in 9:14–29 and thus are the last ones in the book. Nothing overtly miraculous occurs after Chapter 11. (I say “overtly” miraculous because Jesus predicting his death and telling the disciples about the eschaton in Mark 13 are not considered miracles.)

[16] I have tabulated Jesus’s teachings in Mark as those things spoken by Jesus that help the hearer and the crowd interpret what is occurring in the Gospel, as opposed to descriptions about the way things are or will be. Thus, “Before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me three times” from Mark 14:72 is not included, whereas “I am [the Christ], and you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power and coming on the clouds of heaven” from 14:62 is included. Similarly, “Your sins are forgiven” from 2:5 is not included, whereas “But so that you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins…I say to you, rise, pick up your bed, and go home” from 2:10–11 is included.

[17] Mark 1–5 contains approximately 27% of the teachings, Chapters 6–10 contain 35%, and Chapters 11–15 contain 39% (Chapter 16 has no teaching).